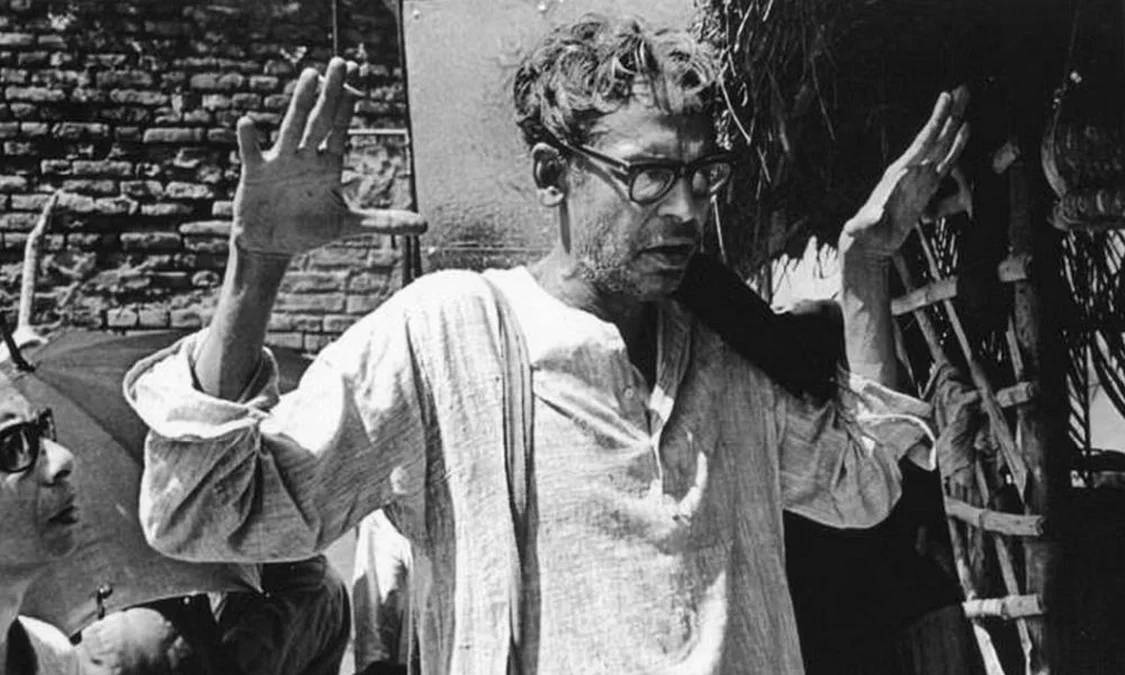

A Century of Ritwik Ghatak

The Visionary Who Gave Cinema a Voice of Exile and Belonging

Author, playwright, and filmmaker Ritwik Kumar Ghatak was born on November 4, 1925, in Narail (now in Bangladesh), to Rai Bahadur Suresh Chandra Ghatak, a district magistrate, and Indubala Devi. During the 1940s, his family, originally from Dhaka, relocated—first to Berhampore, and later to Kolkata. These years of displacement and unrest would come to define Ghatak’s creative consciousness.

As a young man, Ghatak was deeply influenced by the major socio-political upheavals of his time — the Second World War, the Bengal Famine, and the Partition of India in 1947. These events left indelible scars on him, shaping both his worldview and his art. He began writing fiction and plays for the leftist cultural collective, the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), where his work focused on the struggles of the marginalized and the trauma of the uprooted.

Through his plays and later his films, Ghatak became a chronicler of the collective pain of Partition — the migration of millions of Hindus from East Bengal to India, the breaking apart of families, and the gradual erosion of a once-unified Bengali culture.

Between 1958 and 1977, Ghatak directed eight feature films that left an unforgettable mark on Indian parallel cinema. Among them, Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star, 1960), Komal Gandhar (E-Flat, 1961), and Subarnarekha (1962, released in 1965) together form his iconic Partition Trilogy.

These three films portray not just the physical dislocation of refugees but also the spiritual exile of a people cut off from their homeland. In Komal Gandhar, a theatre troupe named Niriksha stages a play about forced migration. An old man asks, “Why should I leave behind this lovely land, abandon my River Padma, and go elsewhere?” His words echo Ghatak’s own anguish over losing East Bengal — a homeland he could never return to.

Later in the same film, when characters Anasuya and Bhrigu stand silently by the riverbank at Lalgola — gazing across the Padma toward East Bengal — their longing becomes a metaphor for the fractured Bengali identity that haunted Ghatak all his life.

Satyajit Ray once wrote in the foreword to Ghatak’s Cinema and I that “thematically, Ritwik’s lifelong obsession was with the tragedy of Partition.” Film scholar Bhaskar Sarkar later described him as “the most celebrated cinematic auteur of Partition narratives.”

Despite being underappreciated during his lifetime, Ghatak’s cinema has since become a cornerstone of South Asian film history. His powerful storytelling, blending realism with myth, sound with silence, and politics with poetry, remains unmatched in its intensity.

Today, on his 100th birth anniversary, Kolkata pays homage to this visionary filmmaker. Six of his masterpieces — Ajantrik, Bari Theke Paliye, Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar, Titas Ekti Nodir Naam, and Subarnarekha — are being screened across the city as part of the centenary celebrations.

Through these retrospectives, a new generation of viewers is rediscovering Ghatak — not merely as a filmmaker, but as a philosopher of displacement, a poet of exile, and a voice of conscience for the divided soul of Bengal.

As the city celebrates his centenary, Ritwik Ghatak’s work continues to remind the world that cinema, at its best, is both art and resistance — an act of remembering what history tries to forget.