Begum Rokeya and Virginia Woolf

Demanding for a ‘Ladyland/Republic for Women’ and ‘A Room of One’s Own’

Both of them were daughters of the late 19th century. One was a brown, Bengali Muslim woman of the colonized India (in the then Bengal Presidency) while the other was a white, Christian woman from the Imperialist Britain. Indians had to fight just 190 years to shake off the iron chains of British Imperialism at the crude, colossal cost of partition in 1947. Millions of people were uprooted overnight and frequent riots caused hundreds and thousands of deaths, rapes, arson attacks and plunders across the sub-continent. Bengal and Punjab suffered the worst.

Adeline Virginia Woolf was born on January 25th of 1882 and committed suicide on March 28th of 1941. One of the most significant, modernist writers of the 20-th century, she picked up the ‘stream of consciousness’ as her chosen form of narrating fiction.

Born in South Kensington, London, into an well-endowed and intellectual family as the seventh child of Julia Prinsep Jackson and Leslie Stephen, Virginia grew up in a family with four siblings from previous marriages of both of her parents and four siblings of her own, including her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell. Her father was an author and mountaineer who allowed Virginia to have total access to his rich library at her adolescence while her mother was altruist. Being educated at home in English classics and Victorian literature along with piano lessons, later she later got admitted into King’s College of London. There she could study classics and history and could meet pioneering advocates for women’s rights and education.

After the demise of her father in 1904, Woolf and her family relocated to the Bloomsbury district, where she joined the renowned literary circle ‘Bloomsbury Group.’ She got wedded to Leonard Woolf in 1912, and the couple founded the Hogarth Press in 1917, which printed lots of her literary work. She ascended to her peak of fame during the interval years of two World Wars through publishing her legendary novels including Mrs. Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927), and Orlando (1928). Her feminist essay A Room of One’s Own (1929), however, inspired feminist literary theorists and critics during the 1970s.

“But for women, I thought, looking at the empty shelves, these difficulties were infinitely more formidable. In the first place, to have a room of her own, let alone a quiet room or a sound-proof room, was out of the question, unless her parents were exceptionally rich or very noble, even up to the beginning of the nineteenth century. Since her pin money, which depended on the goodwill of her father, was only enough to keep her clothed, she was debarred from such alleviations as came even to Keats or Tennyson or Carlyle, all poor men, from a walking tour, a little journey to France, from the separate lodging which, even if it were miserable enough, sheltered them from the claims and tyrannies of their families. Such material difficulties were formidable; but much worse were the immaterial. The indifference of the world which Keats and Flaubert and other men of genius have found so hard to bear was in her case not indifference but hostility. The world did not say to her as it said to them, Write if you choose; it makes no difference to me. The world said with a guffaw, Write? What's the good of your writing?’

Virginia repeatedly emphasized on having ‘A Room of One’s Own’ for any woman aspiring to be a writer. She, an addition, elaborated on her imaginary character of Shakespeare’s sister:

‘This may be true or it may be false--who can say?--but what is true in it, so it seemed to me, reviewing the story of Shakespeare's sister as I had made it, is that any woman born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would certainly have gone crazed, shot herself, or ended her days in some lonely cottage outside the village, half witch, half wizard, feared and mocked at. ---No girl could have walked to London and stood at a stage door and forced her way into the presence of actor-managers without doing herself a violence and suffering an anguish which may have been irrational--for chastity may be a fetish invented by certain societies for unknown reasons--but were none the less inevitable.’

Hats off to Woolf for such assertion!

Now let’s have a look at Begum Rokeya. She was born in the Pairaband Union of Rangpur district on 9th December,1880 to a conservative, landlord family of declining aristocracy. Although Rokeya's father was orthodox in his outlook towards women, his elder brother Ibrahim Saber helped her learn Bengali when it was not permissible for even elite Muslim women to learn anything except the holy Qu'ran in Arabic.

In a comparatively brief span of 52 years’ long life, Rokeya penned near about ten volumes of write-ups, comprising of articles on feminism and other social issues, utopias, novels, poems, and satirical articles. Besides writing, she established a girls’ school for Muslim women and advocated all throughout her life with the patriarchs of the then Bengali Muslim society to make them understand the necessity of women's education.

Rokeya's elder sister Karimunnessa was too an ardent learner of Bengali language and literature. But this 'eagerness to learn' made her parents anxious and she was given away in marriage at the mere age of fourteen. Rokeya too was married off at the age of eighteen in 1898 to a man more than twice her age. He was a widower and his name was Khan Bahadur Sakhawat Hossain. He was posted in a dignified government job at Bhagalpur, Bihar province of India. By the grace of fate, Sakhawat Hossain encouraged Rokeya into learning English, which she managed to grasp very quickly. She was first published as an authoress in 1902 and founded the 'Sakhawat Hossain Memorial Girls' School' in 1909 within five months of her husband's demise. But her step-daughter and step-son-in-law endeavored to generate confusion over the ownership of her property and it compelled her to come to Kolkata from Bihar. In 1911, she re-started the school in her deceased husband's name in Kolkata. Although Rokeya gave birth to two children, none of them survived more than six months.

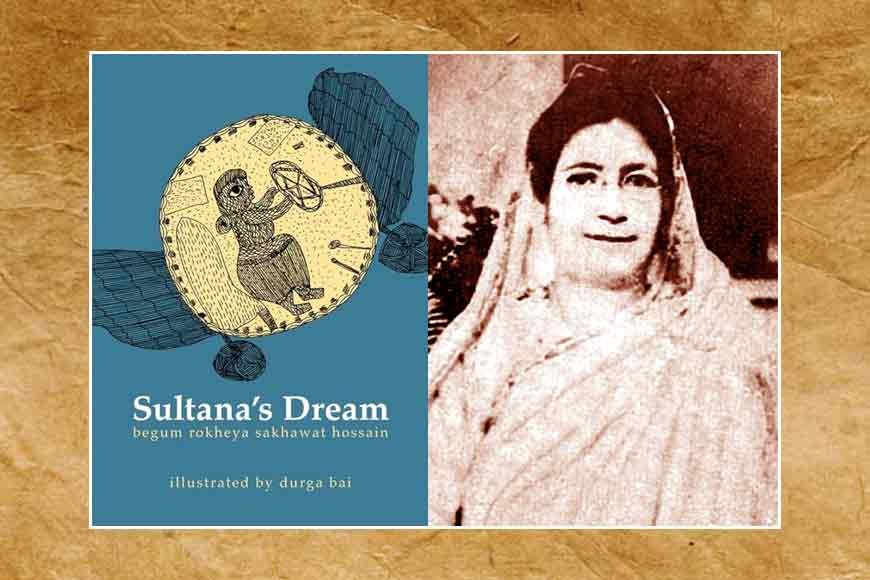

The major books penned by Rokeya are Matichur- first volume (1904, it's a collection of columns in different magazines and newspapers, particularly on women's condition in the then India), Matichur- second volume (1907), Sultana's Dream (authored in English in 1905 and published in 1908), Padmarag (novel, 1924), Oborodh Bashini (Women in Purdah, 1931) and compilations of short stories and utopias. Of them, Sultana's Dream, Padmarag, Oborodh Bashini and Gyanphol (‘Fruit of Knowledge,’ another feminist utopia) are unparallel for their profound insight, humorous observations, critiques of social prejudices and freshness of outlooks.

Interesting thing is Rokeya completed writing Sultana’s Dream in 1905 and her husband, till then alive, gave it to his British supervisor at work to read it. Although the goal was to check her English, the supervisor did not revise a word and just replied, 'What a terrible revenge!' after finishing the novel.

What is most striking that when Virginia Woolf explains the importance of ‘A Room of One’s Own’ for aspiring women authors (1929), Rokeya dreams olf a ‘Ladyland (Naristhan)’ in or a ‘Republic’ for women in 1905! How she had possessed such an invincible courage to dream of a Republic of the women, for the women, by the women, if we re-phrase Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (1863) a bit? Just recall those fiery lines:

`But dear Sultana, how unfair it is to shut in the harmless women and let loose the men.'

`Why? It is not safe for us to come out of the zenana, as we are naturally weak.'

'Yes, it is not safe so long as there are men about the streets, nor is it so when a wild animal enters a marketplace.' ---

Sultana's Dream in Begum Rokeya Rachanabali, 3rd edition (Feb 2010), published by Bornayan.

In this particular feminist utopia, the female protagonist named Sultana visits a faraway lady land (nari rajya) in her dream. She gets accompanied by a lady named Sister Sara. When Sultana walks on the streets of the lady land, she finds no man there and the female pedestrians laugh at her. When Sultana wants to know the cause of their laughing at her, Sara answers that Sultana looks as 'timid and coy' as a man. Later Sultana comes to know from Sara that even fifty years ago this lady land had been just like another male dominated society. But when the last king died and his daughter came to the throne, she took mammoth efforts to educate women, establish women's schools, colleges and universities and particularly endeavored to train-up women in scientific knowledge. Till then the position of the commander-in-chief, all cabinet posts, indeed the power structure, were dominated by men. But, when a war broke out with a neighboring state, the warriors of the country, all men, waged the war with valor but finally could not attain victory. A woman scientist of the country then implored the queen to keep the men at home for some days and let her look into the matter. The wounded and fatigued men did not protest. The lady scientist defeated the enemy army with help of scientific technology and since then the men in that lady land have been staying at home.

This lady land is free from sin and vices, where virtue herself rules. Men are kept in confinement in that cherished lady land to protect the society from crimes like theft, murder, arson, rape, plunder, burglary and so many other evils. The 'logic' of a 'stronger' physical composition of men to dominate women is overruled in that state on the principle that 'a lion is stronger than a man, but it does not enable him to dominate the human race.' As men are confined to mordana (men's secluded area) in that lady land, society no longer needs lawyers in the courts and there’s hardly any warfare or bloodshed. Women look to the official duties and also manage the home as, naturally, better time managers. It needs a woman only two hours to finish office chores as she is seldom a habitual smoker like men (a man smokes twelve cigarettes daily and if one cigarette needs half an hour to be burnt off, he wastes six hours every day in sheer smoking).

Begum Rokeya had passed away on 9th December of 1932.

If we look back at the entire gamut of history of western philosophy, it was Greek philosopher Plato who first advocated for women’s equal opportunity to receive physical training, philosophical studies and music. He studied the behavior of his own parents and observed that while his father was a bit shy and introvert person, his mother had a soldier like attitude in terms of protecting her self-worth and dignity. It inspired him to argue that women too are entitled to hold powerful positions like ‘Guardians’ in the city state and take part in governance of the state, confronting the traditional, gender roles offered to women in the 4th century BC Athens. He, in addition, elaborated that as a she-dog can guard her master’s household like a male dog with no less loyalty or vigilance, women too can guard the city-state like male soldiers. He further elaborated that sometimes even men are born with the aptitude cur of being a cook and women too are seen to born with the aptitude of being an army general. He also demanded for abolition of marriage and personal property and offered a revolutionary idea of communal living for the guardian class where there will be ‘community of children.’ He believed that only this system can prevent corruption and nepotism.

Archaeology of Positivity: Special Lecture of Isabel Herguera, the Director of ‘Sueno de Sultana (Sultana’s Dream)’ held in the Liberation War Museum

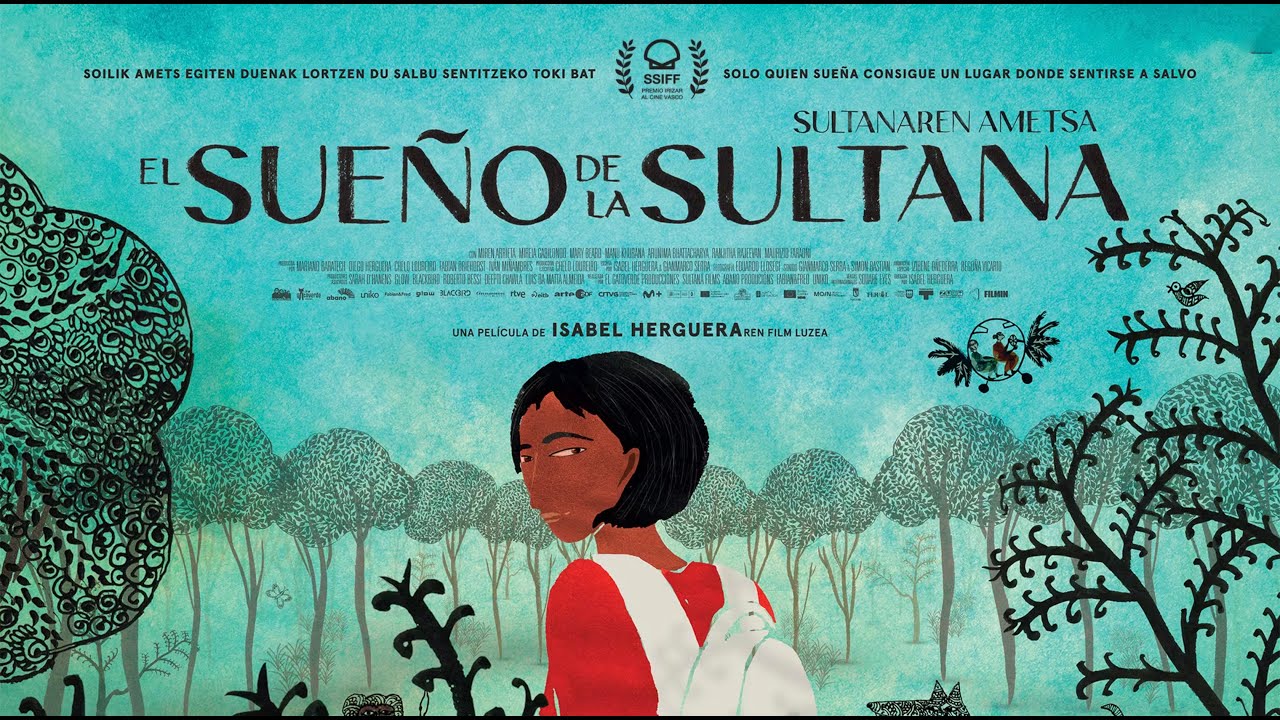

Meanwhile, Bangladesh Liberation War Museum successfully held a special lecture of Isabel Herguera, the Spanish born Director of ‘Sueno de Sultana (Sultana’s Dream)’ on 9th December afternoon at its main auditorium.

Herguera, who has already won more than 50 awards at various international film festivals, graduated from UPV-Bilbao, continued her studies at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1988, and obtained a master's degree at CalArts. In 2005 she started as a teacher at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, India and it was while staying in India that she first found ‘Sultana’s Dream’ at a book shop. Her first feature film, Sultana's Dream, was released in 2023. In this movie she has also merged different techniques to underscore the differences between storylines — watercolor, cut-outs of the shadow theatre and Mehndi. While it was still in the project stage, the film won the 2022 TorinoFilmLab Audience Design Award of the European Work in Progress in Cologne platform and received a €378,000 grant from the Spanish Film Institute.

In the Director’s own words: ‘My encounter with Sultana's Dream , the original story that sparked this whole adventure of making a film, happened by accident. I was seeking shelter during a monsoon storm in New Delhi, India, when I wandered into an art gallery exhibiting works by the Gond tribe. At the back, a red book caught my eye. The cover, illustrated in the Gond style, depicted two women piloting a retrofuturistic spaceship. Intrigued, I approached and read the title : Sultana's Dream: A Feminist Utopia , written in 1905 by Begum Rokeya Hossain. I turned the book over and continued reading: “where the author describes Ladyland , a place where women, possessing knowledge, hold power, while men, deprived of education, stay at home to attend to domestic tasks.

I immediately bought the book, getting lost in the upside-down world called Ladyland, a country where women oversee everything and men stay at home while they take care of the domestic chores, an apologia for intelligence and a combination of brute force. Rokeya Hossain published the short story in 1905 and used science fiction to denounce discrimination against women.’

The Director continued on explaining her journey to Rokeya’s ‘Ladyland’ before a hypnotized audience: ‘I knew immediately that this was the next film I wanted to make. But how to approach it? How to maintain the original atmosphere of the story, full of nuances and references to early twentieth century Bengal, without betraying it by my western point of view? This is when me, my husband and co-scriptwriter Gianmarco Serra and I, came up with the main character Ines, a young contemporary artist from Europe, who is a little lost in the world, and who discovers the book by chance and clings to it like a lifeline, and eventually decides to follow the legacy of the author.’

‘I had some of Rokeya Hossain’s letters and essays translated into English, I also visited her grave in Sodepur and the schools she founded in Kolkata and walked along the landscape of rural Bengal trying to memorize the colors, smells and sounds of Rokeya’s home. This helped me to understand her character and the courage she must have had to confront her society. Her community wanted women to be ignorant and illiterate, but she demanded education for all women, and questioned the religious rules that were imposed upon them by men,’ Isabel added.

Isabel also explained that how much passionate she felt after reading ‘Sultana’s Dream’: It was an ode to intelligence and a condemnation of brute force, written more than a century ago.

I thought about my grandmother, my mother, my sisters, and my nieces, and I asked myself: where are we really today? At that moment, I knew this was the film I wanted to make.

Shortly after, we began organizing art and animation workshops focused on the story. We invited women of all ages, backgrounds, and social conditions to discuss, draw, imagine, and dream about Ladyland , a safe place for women. Little by little, we discovered the heart of the film.

Over the years, we traveled all over India in search of Ladyland and the traces of Begum Rokeya Hossain. We wrote, filmed, drew, painted, kept diaries, and played with puppets under the camera, gradually shaping the universe in which the miracle of the story unfolds.

Sultana's Dream is a film born from the heart, driven by the desire to honor an audience that seeks cinema offering a personal vision of the world. I truly hope you enjoy it.’

The audience came to know from the Director that three workshops were organized with women and particularly adolescent girls in three cities of India. The range of participants covered English medium students to drop-out girls from schools of the poor localities who were trying to survive by taking skill trainings in sewing or henna decoration and it was amazing that the ‘less educated girls showcased more imagination’ than the English medium students. For example, when these girls were told to draw their ‘imagined Ladyland’ after reading out to them the story, a girl drew a ‘pregnant man walking within the water marooned paths of a village during flood.’

This contributor tried hard to catch up Isabel for an interview but the Director is now visiting Pairaband with her team while noted published and one of the Trustee Board members of the Liberation War museum Mr. Mofidul Haque is guiding them in the tour.

‘Beginning of the twentieth century ushered a dawn for women’s emancipation. That era seems like an era of ‘Archaeology of Positivity’, noted the Director.