Poor-Quality School Books Spark Alarm Ahead of 2026 Classes

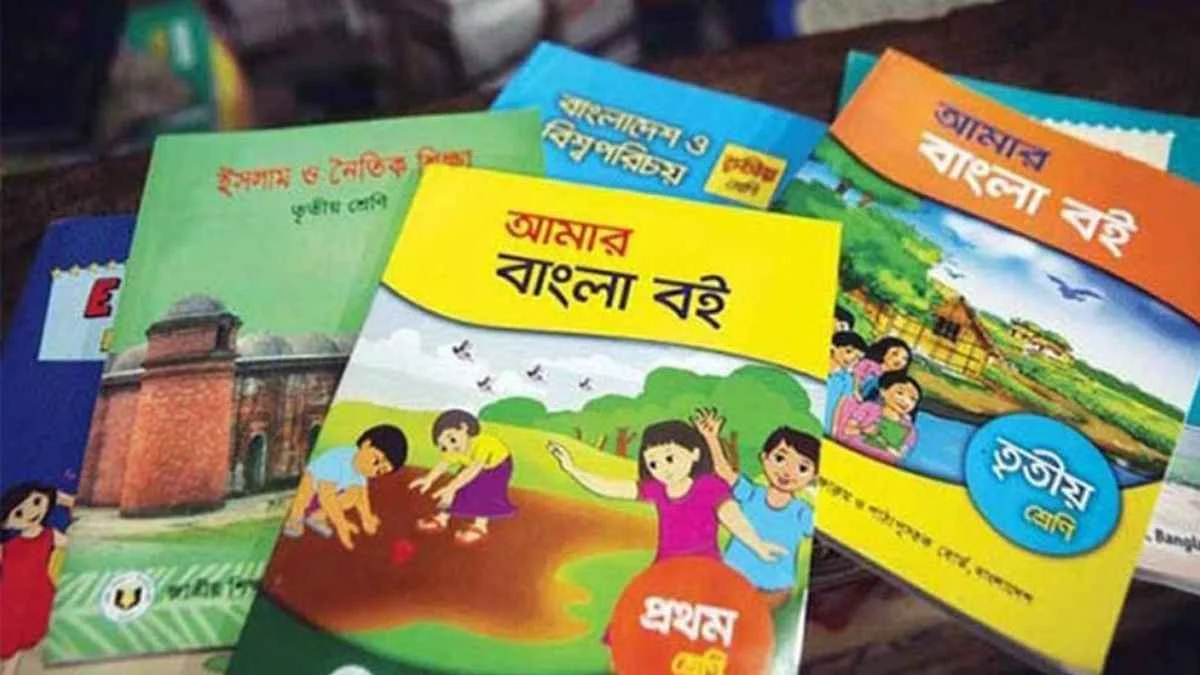

Significant concerns have emerged over the quality of textbooks being printed for the 2026 academic year, as a large portion of the books reportedly fail to meet required standards. Issues range from substandard paper quality to poor printing, raising questions about oversight and accountability within the education system.

Four printing presses in Noakhali—owned by two brothers and their brother‑in‑law—have received contracts worth more than Tk 200 crore for printing the textbooks. These same presses were previously accused of supplying low‑quality books and misappropriating government funds, yet no punitive action was taken, enabling them to continue operations this year as well.

According to specifications, the books were to be printed on 80 GSM paper with 85 brightness. Instead, presses are reportedly using 65–70 GSM paper, with brightness levels failing to reach the required standard. Industry experts warn the resulting books will be thin, fragile, and unlikely to last even six months, potentially straining students’ eyesight.

Market data shows that paper priced at Tk 115,000 per ton is being substituted with recycled paper costing Tk 90,000 per ton. This paper contains only 60–70% virgin pulp, with the remainder made from reused materials—further compromising durability.

Reports also indicate intimidation of officials attempting to inspect the presses. One NCTB (National Curriculum and Textbook Board) official had his bag confiscated upon returning from Noakhali with samples of the substandard paper. Other officials are now reluctant to visit the presses. Inspection agents are allegedly being pressured to test only high‑grade samples, while the actual low‑quality paper used in printing is concealed.

Internal sources claim certain NCTB employees are complicit, using political influence to pressure colleagues into submitting favorable reports despite visible quality issues. In the 2025 academic year, around 80% of textbooks supplied by these presses were deemed substandard, but investigations stalled and no corrective measures followed.

Members of the printing industry argue that the syndicate behind the scheme has misappropriated hundreds of crores of taka in previous years. By lowering paper quality alone, they have reportedly siphoned off significant portions of government funds. Critics point to insufficient action from the Ministry of Education and the NCTB in preventing these recurring irregularities.

Currently, nearly 300 million textbooks are being printed nationwide. If a substantial share of these are of poor quality, experts warn that the entire academic year could be adversely affected. Students may struggle with fragile books, while parents could be forced to purchase replacements.

Education specialists emphasize that immediate action is necessary to dismantle the syndicate and ensure accountability. They urge the government to enforce stricter monitoring, penalize suppliers of low‑quality textbooks, and take disciplinary action against internal collaborators within the NCTB.

They stress that textbooks are not merely paper and ink—they are critical tools for learning and nation‑building. Substandard books risk harming an entire generation of students.