Bangladesh’s Human Rights Landscape: How Long Will Impunity Continue?

Each year, December 10 serves as a global reminder that human rights are not abstract ideals but lived experiences—either upheld or denied. This year, however, Human Rights Day arrives at a critical juncture for Bangladesh.

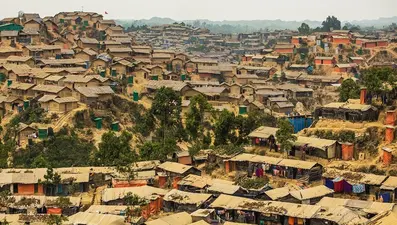

The political upheaval of 2024, the breakdown of long-entrenched governance structures, and the rise of a fragile interim framework have laid bare an uncomfortable reality: Bangladesh’s human rights system is institutionally fragile. Without a sincere commitment to reform grounded in transparency, accountability, and institutional integrity, the nation risks replacing one cycle of abuses with another rather than breaking free from it.

A constructive conversation demands something beyond condemnation. It requires grounding facts from Bangladesh’s own human rights organizations, assessments from credible international bodies, and an honest examination of how governance culture—not just governments—determines whether rights survive.

For nearly two decades, human rights in Bangladesh have moved in tandem with political interests rather than constitutional obligations. The country’s leading rights groups—Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), Odhikar, the Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST), and the Human Rights Forum Bangladesh—have repeatedly warned that arbitrary arrests, custodial abuses, enforced disappearances, and restrictions on expression were becoming “normalized tools of governance.”

ASK’s reports between 2014 and 2023 documented: Over 1,800 extrajudicial killings, mostly in the name of anti-drug or anti-terror operations. More than 600 cases of enforced disappearance, with a consistent pattern of denial and intimidation. Hundreds of attacks on journalists, including legal harassment, arbitrary detention, and digital censorship.

The Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), in a press release published on 7 August 2025 titled “One Year of the Interim Government: A Persisting Human Rights Crisis,” reported that serious human rights violations have continued under the interim administration.

According to the statement, human rights abuses have taken a severe turn even after the interim government took office following 5 August 2024. Ain o Salish Kendra has noted that the interim government has disappointed the public by failing to fulfill their expectations. ASK states that arbitrary arrests, custodial deaths, and extrajudicial killings are still occurring—signs of a troubling continuity with the repressive practices of the previous government. Additionally, a growing deterioration in law and order has heightened citizens’ concerns about personal safety.

The press release further notes a worrying rise in ‘mob violence’ across the country. These violent incidents—often triggered by political provocation or social tensions—have left numerous people dead or injured. ASK observes that state law-enforcement agencies and responsible institutions have failed to play an effective preventive role, raising serious concerns for human rights protection.

Another alarming trend, according to ASK, is the increasing vulnerability and lack of protection for religious minorities. Citizens had expected the interim period to usher in an inclusive and rights-respecting governance framework. Instead, attacks, intimidation, and persecution against religious and ethnic minority communities have intensified.

ASK also highlights that the situation has become even more precarious for women, who were at the forefront of the recent mass movement. The organization notes that women are now living in an atmosphere of pervasive insecurity. Incidents of women being beaten, humiliated, and physically assaulted in public spaces have risen sharply. Reports of rape, sexual harassment, and domestic and social violence have become disturbingly routine. The surge in hate speech targeting women, attempts to police their clothing or behavior, and escalating acts of “moral policing” point to what ASK describes as a form of structural violence—one that is shrinking the social, political, and economic space necessary for women’s empowerment.

ASK further states that the media is facing various forms of harassment, with increasing pressure on journalists and news organizations. Meanwhile, violations of students’ rights have also been reported. Many students have been unjustly expelled, had their certificates cancelled, or faced institutional retaliation—developments the organization deems extremely concerning.

Odhikar’s data, though severely restricted in recent years due to government pressure, echoed the same patterns. The organization’s 2022–2023 reports flagged increasing politicization of law enforcement, weaponization of digital laws, and systematic suppression of dissent.

International bodies corroborated these findings. The UN Human Rights Council, OHCHR, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International frequently raised concerns over Bangladesh’s recurrent lack of accountability. Recently, OHCHR described the human rights situation in Bangladesh as exhibiting “patterns of impunity” rooted in institutional unwillingness rather than lack of capacity.

The rise of the internet brought promise—but also unprecedented surveillance and legal repression. Bangladesh’s Digital Security Act (DSA) became one of the region’s most controversial laws. Between 2018 and 2024: Over 4,000 cases were filed under the DSA. Journalists, writers, cartoonists, students, activists, and even citizens expressing personal opinions were criminalized. According to the Centre for Governance Studies (CGS), about 60% of DSA cases were politically motivated.

Even after the law was rebranded as the Cyber Security Act (CSA) in 2023, the core problems persisted. The law retained vague definitions, sweeping police powers, and broad criminalization of speech—prompting both local and international rights bodies to assert that it simply rebranded repression instead of reforming it.

Human Rights Watch noted in its 2024 assessment that the CSA “fails to correct the DSA’s fundamental threat to free expression.” Bangladesh’s domestic journalist unions and press freedom networks made similar observations: without independent investigative protocols and judicial oversight, digital regulation will remain a pressure tool rather than a protection framework.

The high-intensity human rights violations are: enforced disappearances, extrajudicial Killings, and custodial torture. Local organizations reported hundreds of cases, many involving political activists. Families described consistent patterns: plainclothes men, unmarked vehicles, midnight detentions, and subsequent silence. Some victims later resurfaced in police custody; others were found dead; many remain missing. UN Working Groups repeatedly urged Bangladesh to allow independent investigations, but such requests were refused or ignored.

The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB)—once celebrated for counter-crime operations—became internationally scrutinized for the frequency of ‘crossfire deaths’. Though the frequency declined after U.S. sanctions in December 2021, ASK and HRW both reported a persistent pattern of custodial deaths and unexplained fatalities attributed to law enforcement even after the sanctions.

Despite the 2013 Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention) Act, implementation remains weak. The Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) noted that few complaints result in prosecution, victims fear retaliation, law enforcement enjoys institutional and political protection.

Bangladesh’s media environment, once vibrant and pluralistic, has deteriorated into a landscape of fear-driven compliance. Domestic press councils, international watchdogs like the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), and Reporters Without Borders (RSF) consistently highlight: surveillance of newsrooms, pressure on editors, smear campaigns against critical journalists, ownership structures aligned with political interests, increased self-censorship out of economic and legal fear.

Civil society organizations faced similar suffocation. Restrictions on registration, funding, and reporting—particularly the Foreign Donations Regulation Act—were used to control and punish watchdog bodies.

Odhikar became the clearest example: its registration renewal was denied, its leaders prosecuted, and its operations crippled for publishing data that contradicted official narratives. The message to civil society was unmistakable.

The fall of the Awami regime on 5 August 2024 has created an opportunity—but also risk. Transitions often trigger either democratizing reforms or intensified repression under new justification. The interim government has failed in that regard, and its consequences are now visible across Bangladesh. Bangladesh’s interim government now faces a dual test: 1) Break with the culture of impunity, not just the personalities involved. 2) Show that rights protection is a system of governance, not a slogan of convenience.

Signs are mixed. Some political prisoners have been released; some legal reforms have been initiated. But concerns remain:

• CSA continues to be used selectively.

• Law enforcement reforms are slow and unclear.

• No independent commission has yet been empowered to investigate past violations.

• Political polarization threatens to reproduce the old cycles of revenge rather than establish rule of law.

If Bangladesh wants to step beyond the international ‘high-risk’ human rights category, three strategic interventions are non-negotiable. These include:

Establish an Independent Human Rights Accountability Commission: A body with constitutional protection, mandate to investigate disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and custodial torture, powers to summon officials and demand records, independent forensic capability, international observers for credibility

Rebuild the Legal Architecture of Expression: This requires repealing vague clauses of the CSA, eliminating pre-trial detention for expression-related cases, creating a judicial oversight panel on digital policing, ensuring civil society participation in drafting future cyber laws. A nation that criminalizes criticism criminalizes progress.

Reform Law Enforcement with a Professionalization Agenda: Accountability must be paired with modernization such as mandatory body cameras, independent internal affairs division, human rights training integrated into promotion criteria, zero-tolerance policy for custodial torture, transparent reporting of all law enforcement operations. Professionalizing the force is not anti-state—it is pro-stability.

Human Rights Day this year is not just a ceremonial observance for Bangladesh—it is a strategic pivot point. The nation’s demographic strength, economic ambitions, and geopolitical centrality cannot be sustained alongside systemic rights violations. Investors look at rule of law. Diplomats look at accountability. Citizens look for safety and dignity. None of these flourish in an opaque environment. Bangladesh stands at a crossroads: reinvent its human rights culture, or continue cycling through crisis and correction.

Despite the grim patterns, Bangladesh’s human rights movement remains resilient. Journalists who continue reporting despite intimidation, families who speak up about disappeared relatives, rights workers who persist despite prosecution—these are not signs of a broken nation. They are signs of a nation unwilling to surrender its conscience.

Human Rights Day, therefore, should not be a reminder of failures but an invitation to build a different future—one where human dignity isn’t conditional, contested, or politically negotiable. Bangladesh can choose to build such a future. It has the institutions, the civil society, and the legal frameworks. What it needs is political will and courage. And courage, unlike rights, cannot be legislated. It must be exercised. Human Rights Day 2025 should catalyze that exercise—so Bangladesh can finally shift from a reactive posture to a proactive, principled, and globally respected rights governance model.

In the ongoing worldwide ordeal of turbulence and unpredictability, where many feel a growing sense of insecurity, disaffection and alienation, the theme of Human Rights Day is to reaffirm the values of human rights and show that they remain a winning proposition for humanity.

Through this campaign, we aim to re-engage people with human rights by showing how they shape our daily lives, often in ways we may not always notice. Too often taken for granted or seen as abstract ideas, human rights are the essentials we rely on every day.

By bridging the gap between human rights principles and everyday experiences, we aim to spark awareness, inspire confidence and encourage collective action.

The campaign emphasizes that human rights are positive, essential and attainable.

Emran Emon is a Sub-Editor at

The Asian Age.