Isabel Herguera on Art, Feminism, and Begum Rokeya

“Sultana’s Dream Lives in All of Us, Women’s Empowerment Transcends Borders”

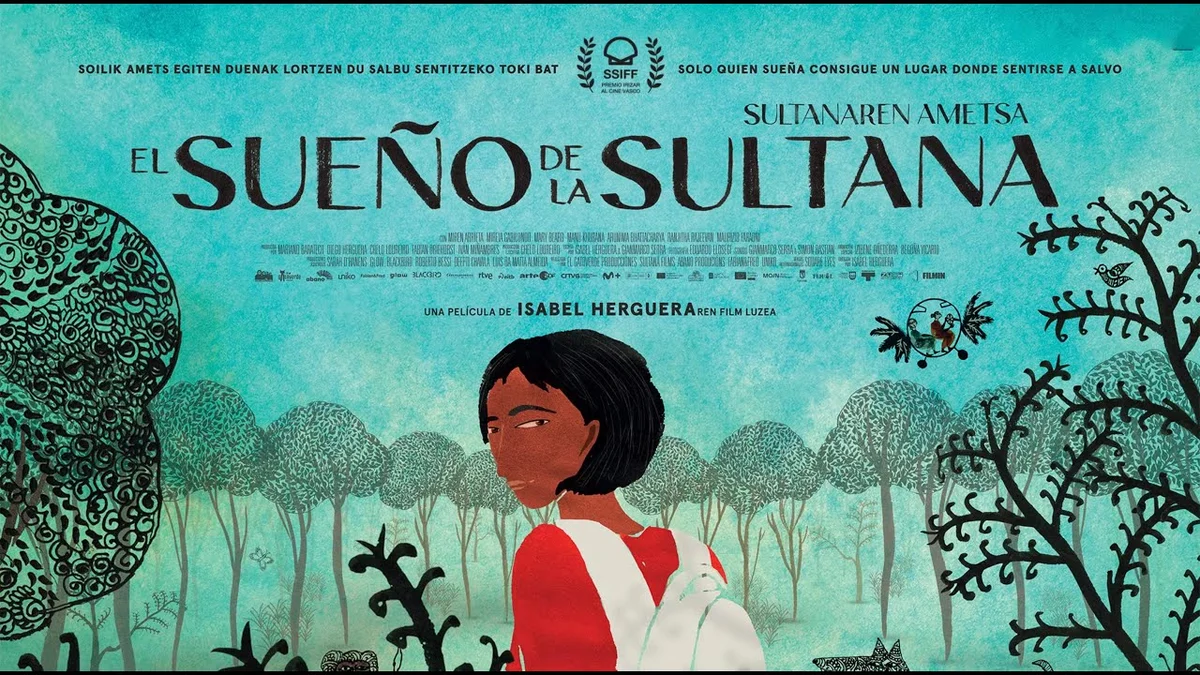

Born in 1961, Isabel Herguera comes from San Sebastian, a border town between Spain and France. This Spanish artist, filmmaker, cultural manager, professor, and critic so far has won more than 50 awards at various international film festivals. Graduated from UPV-Bilbao, she continued her studies at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1988, and obtained a master's degree at CalArts. In 2005 she started as a teacher at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, India and it was while staying in India that she first found ‘Sultana’s Dream’ at a book shop. Her first feature film, Sultana's Dream, was released in 2023.

This film director has recently visited Bangladesh during 7-14th of December, held two lecture sessions on her encounter with Begum Rokeya in the Liberation War Museum of Dhaka on 9th and 13th of December and took a trip up to Pairaband in Rangpur, i.e., Begum Rokeya’s birthplace. BD Voice feels delighted to publish her interview for our readers).

Was this your first visit to Bangladesh? How did it feel? We understand you also visited Paraiband, Begum Rokeya’s birthplace. How long did you spend there?

This has been my first visit to Bangladesh, and it has exceeded all my expectations. The warmth and generosity with which I have been received has been especially moving. I spent a day in Paraiband, visited the birthplace of Rokeya Hossain, touched the stones of the house and an ancient tree, which I imagine witnessed the childhood of Begum Rokeya. I felt as though I had finally reached the end of this journey.

Were you able to interact with ordinary women in Paraiband?

I was able to meet some women in Paraiband, women who had grown up with the writings of Begum Rokeya. Yes, I met her heirs in both thought and spirit.

Considering this was your first visit to Bangladesh and Paraiband, do you think visiting before making Sultana’s Dream would have influenced the film differently?

I don’t know about what could have been if I would have come before making the film. Probably it would have been another film. But what I do know is that Sultana’s Dream lives in each one of us. Regardless of whether we visited her birthplace or the surroundings where Rokeya grew up, I believe what was important was to make Rokeya’s story a personal mission. We needed to bring Rokeya’s teachings into our space today, within each of our languages and cultural and social backgrounds. Begum Rokeya’s message is universal. Reaching Paraiband at the end of this journey has been an honor and a great reward for me.

In your ‘Director’s Note’, you mentioned that reading Sultana’s Dream inspired you to make the film and reflect on women’s lives, including those of your mother and sister. Even though women in the West often enjoy more freedoms, do you think there are common challenges that women face worldwide? If so, what are they?

The search for a place where women can feel safe is something common to all of us. The fear of walking down a poorly lit street is common to all of us. Certain traditions, the references on how women should behave, are behaviors inherited from a patriarchal system that is constantly being questioned.

Whether you come from the East or the West, whether you come from a socially privileged place or not, those of us who have the privilege of accessing information have the tools to confront these beliefs. Therefore, it is our obligation to make them visible for those who do not have the resources to do so.

Why did you choose animation as the primary medium for your film? Films like George Orwell’s Animal Farm or Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis which narrated the story of women’s condition in Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, have also used animation to tell politically or socially significant stories. What was your ‘Raison d’Etre’ or logic of choosing animation as your preferred form of film?

I am an animator and have been working in this field for over 30 years. I know the tools and means of expression, and I feel very comfortable in it. Drawing and painting, allows me to tell stories that otherwise I wouldn’t have the courage to tell. The animated film Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi was a great source of inspiration.

You mentioned conducting three workshops in India before making Sultana’s Dream. Were those workshops aimed at non-Bengali-speaking women and girls?

Yes, I conducted workshops with different women in India as well as in Spain, with non-Bengali and non-English speaking participants. Initially, I translated the story into both Spanish and Gujarati. The story has a simple but very powerful premise: turn the roles around and imagine... This very simple reversal opens a wonderful door to reimagine the world and your place in it.

You translated Sultana’s Dream into Spanish and Gujarati. Does that mean you speak Gujarati? How long did it take you to learn it, and did you notice any similarities between Gujarati and Bengali?

Unfortunately, I don’t speak Gujarati, so I asked a good friend of mine to translate it. That way, during the first workshop we had with the mehendi ladies in Ahmedabad, we could read the story in their own language. Despite not knowing the language… yes, I can feel certain similarities but also differences in the sounds of each language.

In one of your workshops, an adolescent girl drew a “lady land” where pregnant men walked through flooded rural roads. Was this in Gujarat, and did you ask her about the concept behind her illustration?

I mentioned how different, free, and open young girls are in the way they think, and how, slowly but steadily, as we approach adolescence, girls become much more aware of social rules and customs, turning more cautious and less spontaneous and imaginative. Young girls imagined a world where men are pregnant and shy, and women travel to Saturn and have beards.

Was at least one of these workshops conducted in West Bengal?

One workshop I did in Kolkata in 2019, and as soon as they heard about the story, all the women loved it and came up with wonderful ideas. It felt like they had been waiting to hear a story like that in order to let their imagination soar.

You’ve visited Rokeya’s grave in Sodepur, her school in Kolkata, and rural landscapes in Bengal. Do you think South Asian women share similar perceptions about life despite linguistic differences? How would you compare rural West Bengal with Paraiband in Bangladesh?

The everyday lives of women are defined by their landscapes, the nature, the sounds, and the languages that surround them. But their profound desires, pains, and concerns, as reflected in Sultana's Dream, are pretty much the same: a desire to be in command of their own lives, a desire to make decisions, and a concern for their safety, as well as for the safety of their daughters and other women. Understanding women's empowerment goes beyond languages, landscapes, flags, and borders. This, I believe, is the message that Rokeya Hossain wanted to convey.

Your husband is also a co-writer and handles sound direction in your films. How did you meet, and how did your collaboration begin?

At that time, I was the director of Animac, an animation festival in Spain, and I invited a group of Italian artists to hold a workshop called Cucinema. The workshop consisted of painting on raw, clear 16mm film, creating the sound for it, and making and cooking pasta for dinner. The workshop lasted around 4 hours, and by the end of it, you watch the film and have dinner. He was one of the artists who organized the workshop. We met there and have been together since.

Would you like to share how you met him, how many projects you’ve done together, and, yes, is he an Italian?

I met Gianmarco in February 2008 in Spain. At the time, I was the director of the animation festival Animac, Mostra Internacional de Cinema d’Animació de Catalunya, in Lleida, and I had invited a group of Italian artists to teach a workshop. The workshop involved painting directly on film, creating the soundtrack, and cooking pasta at the same time. At the end of the workshop, you would watch the film you had made and share dinner together. Gianmarco was one of the sound artists in the Italian group. Since 2010, we have worked together on around eight short films. We have taught workshops together and written scripts we co-wrote the script for Sultana’s Dream. We eventually got married and continue to live and work together.

Could you tell us about your childhood in Spain and how you developed your passion for film and animation?

I grew up in San Sebastián, a small city in the north of Spain. I loved to read and watch movies, but I never thought of becoming an animator. I discovered animation thanks to a friend of mine, Gul Ramani, originally from India. He put a 16mm camera in my hands for the first time and taught me how to use it. I remember it was love at first sight. I had a wonderful time making my first film, which I made using cutouts. It was a film about my family and growing up in Spain during the time of the dictator Franco. I remember feeling very free and full of ideas. I had the feeling that making movies was a bit like playing with toys and telling stories to my younger siblings, just like when I was a kid.

Your first animation film, Spain Loves You (1987), was inspired by your family and life under Franco’s regime. Could you briefly describe its storyline?

My first animation film, titled Spain Loves You (1987), was inspired by a family photograph of my parents and my five siblings. It deals with growing up during the decade from 1965 to 1975, a time when one becomes aware of many things among them the birth of my twin brother and sister, the first man landing on the moon, and the constant police surveillance in the border town where I grew up, between Spain and France.

You’ve worked across the globe—in China, India, and the USA. Has this mobility affected your personal or family life? Do you have children?

There is no single way to understand family. I have a large family—those related by blood, but my family also includes friends, partners, siblings, cousins, and even people you meet for just a few hours on a train ride. Family is a term that defines the people you love, the ones with whom you feel at ease and at home. I also recently found my family here in Dhaka.

And no, I don’t have children. It’s a decision I made because I wanted to be free, travel the world, and make art. I never felt the desire to have children of my own. I have nieces and nephews, and I am a teacher, so in that sense, I have plenty of kids.

Finally, do you plan to work on any other projects inspired by Begum Rokeya in the near future?

Rokeya and her legacy will always be present in my work and in my life. That is a commitment I intend to honor in whatever work I do.