Laldiya Terminal Agreement: Government Fails the Test of Transparency

There is a proverb that says the sticks of the drum remain with the drum. After the July mass uprising, there was an expectation that transparency and accountability would be the foundation of the new administration’s work. But unfortunately, like the proverb, that did not happen.

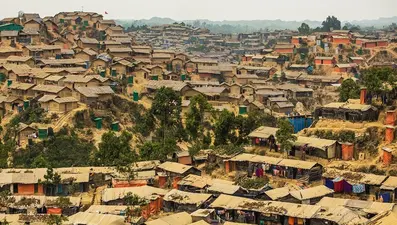

The government’s rushed 30-year agreement with Denmark’s APM Terminals for the construction, financing, operation, and management of the Laldiya Container Terminal in Chattogram seems to be proof of that.

The timing chosen for signing the agreement and the negligible amount of information disclosed about its terms appear to “coincidentally” align with the irregular 25-year power purchase agreement made with India’s Adani during the tenure of the fallen government.

There is no doubt that to sustain Bangladesh’s development, modernization of the Chattogram port is essential, and the construction of an ultra-modern container terminal is part of that. But the way this agreement has been executed has generated clouds of suspicion and created a troubling precedent for the future.

The origins of this agreement trace back to an unwelcome proposal in 2023 from the Maersk Group, the parent company of APM Terminals—approved by Sheikh Hasina in her capacity as Prime Minister.

On January 3, 2014, at the first Bangladesh–Denmark Joint Platform meeting, APM Terminals’ formal proposal for Bangladesh was accepted. Within six months, the PPP Authority appointed the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group as the transaction advisor for the project through a direct procurement method—despite the best practice for such appointments being a tendering process.

Less than two months after this appointment, the Awami League government was ousted by the mass uprising, and the interim government led by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Professor Dr. Muhammad Yunus assumed responsibility. After taking power, the interim government undertook the initiative to cancel the non-competitive agreements signed during the Awami League regime, with the goal of ensuring the best possible opportunities for the public.

In the subsequent period, many agreements awarded without competitive bidding were not renewed. Several renewable energy agreements, the floating LNG terminal agreement with Summit Group, and the contract for appointing a Chinese contractor to operate the country’s main crude oil import facility were canceled.

To set an example of transparency and accountability, the government issued a fresh tender for the operation and maintenance of the 8,300-crore-taka Single-Point Mooring (SPM) terminal near Maheshkhali. Although the SPM-construction firm China Petroleum Pipeline Engineering Company was supposed to be given the opportunity to operate it under a special provision of the Energy Act, they were instead instructed to participate in the open bidding process.

Given the interim government’s visible commitment to fairness, it would have been reasonable to assume that port-related agreements made during the previous administration were being reviewed. But surprisingly, that was not done. Instead, these long-term agreements are being finalized hastily, even before the current term expires in February.

The Laldiya agreement is one such unfair contract from the Awami League era that the interim government has finalized.

According to international practice, such unsolicited proposals should be placed under a “Swiss Challenge” process—where transparency, competition, and maximum value for the public interest are ensured. Under the Swiss Challenge method, when the government receives an unsolicited proposal, it requests alternative proposals, and after receiving the best counter-proposal, the original proponent is given the opportunity to match or improve upon it.

Unfortunately, the interim government did not choose this path and instead opted for direct procurement—which, while legal, is not the best practice.

Then comes the nature of the contract—its duration is 33 years, with the possibility of extending it by another 15 years if performance targets are met. For such long-term investments, high-level political commitment is essential because political changes or influential interest groups can obstruct project implementation. Therefore, the best approach is to present the rationale for a PPP project convincingly and transparently from the outset, so that broad political consensus can be secured and short-term political pressures can be managed.

Unfortunately, from statements by the two major political parties of the present—BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami—it appears that the interim government did not involve them in this process. Yet after the coming election, either of these two parties is likely to form a coalition with smaller parties and take power, and the agreement with APM Terminals will come into effect only after they assume office. The intent behind making a decision while keeping them in the dark about the terms of the agreement is unclear, and it clearly exposes a lack of accountability—something unexpected from the interim government.

The speed at which the agreement was signed further fuels suspicion. The Chattogram Port Authority (CPA) completed all procedures within just two weeks—something that sounds unbelievable in the context of Bangladesh.

APM Terminals submitted its technical and financial proposals on November 4; on November 5 the technical proposal was evaluated, and on November 6 the financial proposal was evaluated and discussions began the same day. On November 7 and 8—during the weekly holidays—discussions between CPA and APM Terminals were completed. On November 9, the CPA board approved the proposal and forwarded it to the Ministry of Shipping, and the next day it was sent to the Law Ministry.

On November 12, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) approved the final proposal. The Chief Adviser granted final approval on November 16, and on the same day, the Letter of Award (LoA) was issued to APM Terminals.

Typically, the contract is signed at least two weeks after issuing the LoA. But the Laldiya Container Terminal agreement was signed on November 17—the very next day—when the entire nation’s attention was focused on the verdict against Hasina in the crimes against humanity case.

Then comes the question of disclosing the terms of the agreement. Usually, such contracts include confidentiality clauses. However, governments in many countries are increasingly taking proactive steps to increase transparency and avoid future complications by disclosing contract information.

Neighboring India attempts to disclose as much information as possible regarding PPP agreements. In several Latin American countries such as Brazil, Chile, and Peru, broad active-disclosure policies for contracts have already become a standard. The United Kingdom has adopted a disclosure-focused policy; Australia and Canada also publish critical information related to their projects and agreements.

In short, there is a clear global trend toward disclosure to ensure transparency in PPP projects. Even if the entire agreement is not published, many countries have begun the practice of releasing simplified summaries of the agreements.

But in the case of the Laldiya agreement, the interim government has kept the entire process secret by invoking the confidentiality clause of the PPP Act 2015. This act was passed by the Awami League government and contains severe gaps in transparency.

Moreover, the argument that information cannot be disclosed due to the confidentiality of pre-contract activities under Section 34 of the PPP Act is misleading.

This section applies only to pre-contract activities and explicitly states that the provisions of the Right to Information Act 2009 shall prevail. That means the government was obligated to disclose information even during the pre-contract stage. More importantly, once an agreement is signed, it becomes a public document, and there is no legal barrier to its disclosure.

In this case, it is entirely possible that the agreement protects national interests and may even be a strong agreement. But had the public been included in the process, the importance of this potentially milestone-setting agreement would have been further enhanced.

In reality, the interim government has continued the same secrecy-driven actions as the previous government’s misrule—creating a dangerous precedent for future elected governments.

Source: The Daily Star