The First Document of the 1971 Genocide: The Report That Changed History

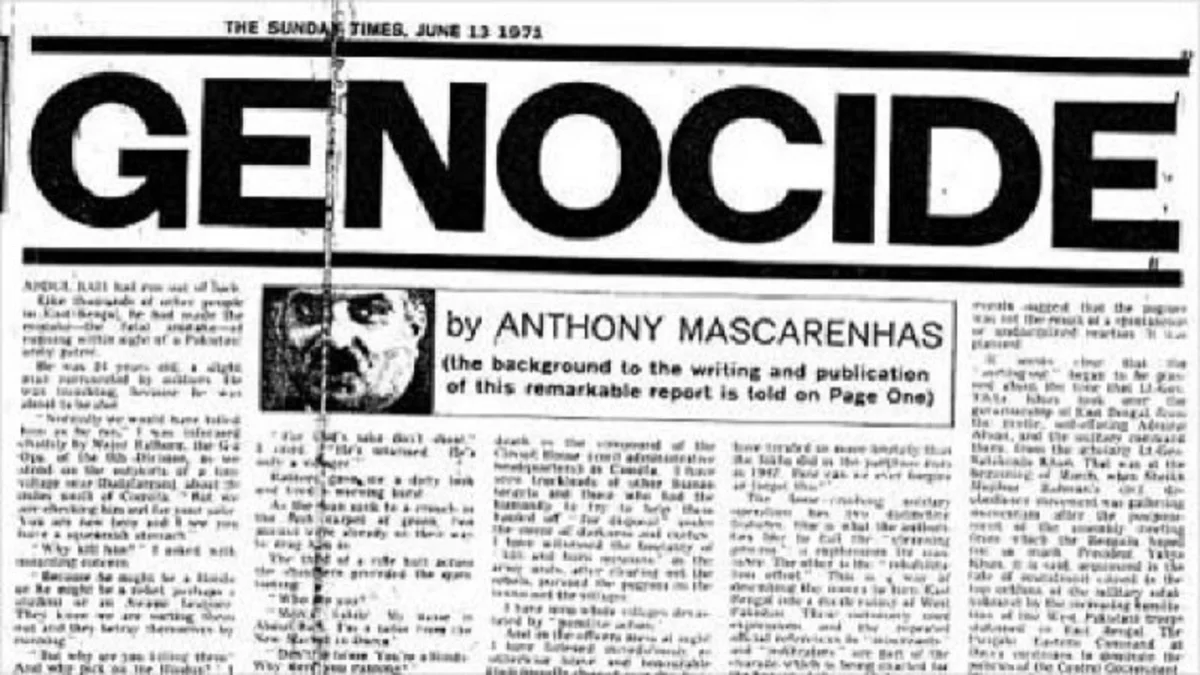

On June 13, 1971, a single report published in the United Kingdom’s The Sunday Times changed the history of South Asia. The report exposed to the world stage the brutal attack carried out by the Pakistani forces in East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh). The reporter’s family was forced to flee at the time, and with this report began a journey that would turn the course of history.

“Abdul Bari was not fortunate that day. Like thousands of people in East Bengal, he too made a fatal mistake—running within the line of sight of a Pakistani patrol. The soldiers surrounded the 24-year-old, thin-built man. Abdul Bari was trembling with fear. He understood that he was about to be shot.”

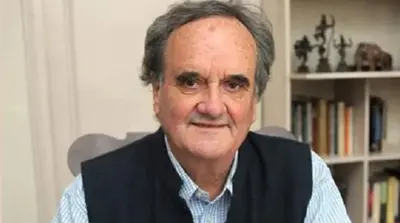

With this scene began one of the most influential reports in the history of South Asian journalism. The author was Pakistani journalist Anthony Mascarenhas. His writing in The Sunday Times revealed for the first time the scale of genocide carried out by the Pakistani army in East Pakistan, akin to a ‘Final Solution’.

Mascarenhas’s report turned global opinion. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi publicly stated, “The report stunned me so profoundly that I became preoccupied with preparing the ground for Indian military intervention in Europe and Moscow.”

Before the publication of this report, Pakistan’s military junta had effectively expelled foreign journalists from East Pakistan. Due to a media blackout in the then East Pakistan, the world was still completely in the dark about the horrors of the genocide. Pakistani soldiers took foreign journalists on brief tours of East Pakistan to show their ‘victory’ over the ‘Muktis’. Eight journalists went on the tour, and Mascarenhas was among them as a well-known journalist from Karachi.

Mascarenhas did not write what the other Pakistani journalists were compelled to write. Instead, he described the ‘most barbaric savagery’ he witnessed with his own eyes, as well as officers proudly boasting in army camps about their ‘day-long hunts’.

Mascarenhas’s wife, Yvonne, recalled, “I had never seen my husband so devastated before. He was completely stunned by mental pressure. He told me that if he could not write what he had seen, he would never be able to write another word in his life.”

Mascarenhas knew that publishing the horrific genocide he had witnessed in any Pakistani newspaper was completely impossible. If the report were published, he would almost certainly lose his life.

As an objective reporter, Mascarenhas had fulfilled his duty with integrity that day. Under the pretext of visiting his ailing sister, he traveled to London, risking his own life and that of his family, and contacted The Sunday Times. He presented an eyewitness account of the genocide that Pakistani military officers themselves described as a ‘final solution’.

For the safety of his family, he sent a coded message to his wife under extreme secrecy and left the country via Afghanistan. The very next day after reuniting with his family in London, the historic report was published, bearing a title of just one word—“Genocide”.

To Pakistan, this report amounted to the ultimate act of betrayal. Mascarenhas was accused of being an ‘enemy agent’. However, he had been so close to Pakistani officials that no one doubted his experiences and eyewitness accounts. Pakistan still denies responsibility for the genocide committed during the Liberation War, labeling it as Indian propaganda.

In Bangladesh, Anthony Mascarenhas is still remembered with deep respect. The report is still on display at the Liberation War Museum in Bangladesh. Trustee of the Liberation War Museum, Mofidul Hoque, said, “When our country was completely cut off from the world, this report helped inform the world about the situation here.”

Mascarenhas’s family began a new life in London. Recalling those days, Yvonne said, “Our life there was completely different from Karachi. We hardly knew anyone. We tried to remain cheerful. But we never regretted the decision.”