No Election Atmosphere in the Hills

Competition and Participation Fade in the Absence of Regional Parties

While other districts of the country are witnessing campaign activities, posters, banners, and rallies centered around the National Parliamentary Election, the picture in the three districts of the Chittagong Hill Tracts Rangamati, Khagrachhari, and Bandarban is completely different. There is no electoral heat here, nor any indication of strong competition. Speaking with local voters, journalists, and election-related officials, it has been learned that this year’s election in the hills has become largely “bland,” lacking interest and one-sided.

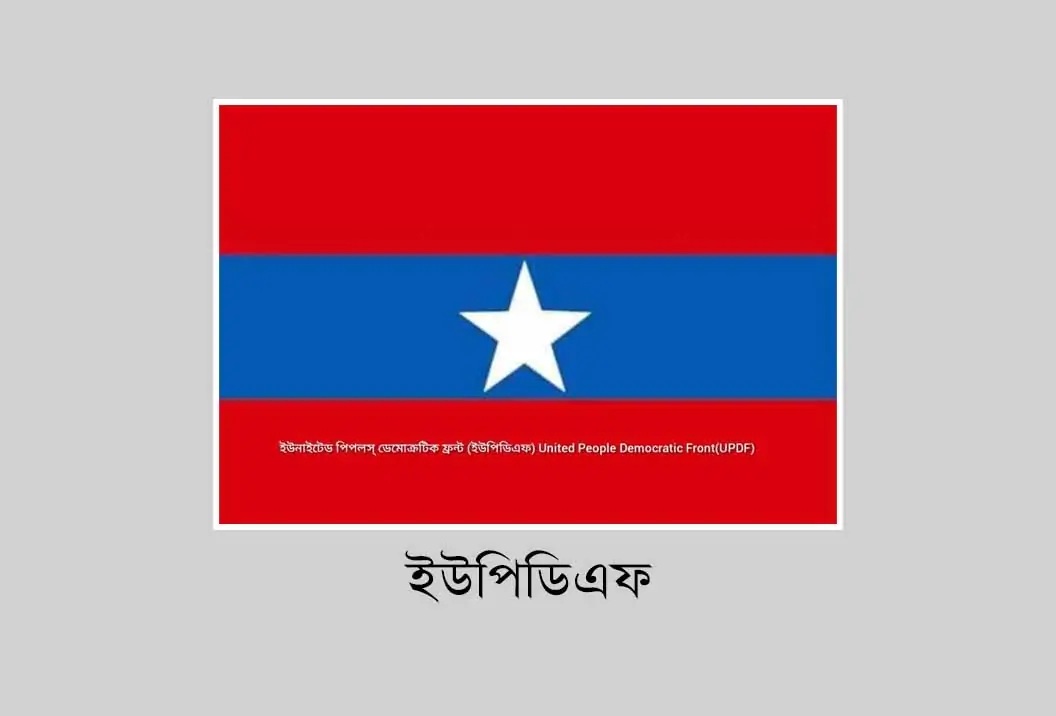

The main reason behind this is the absence of regional political parties. The three influential organizations in the hill region Parbatya Chattogram Jana Samhati Samiti (JSS), United People’s Democratic Front (UPDF) and its two factions UPDF (Prosit Khisa) and UPDF (Democratic)—are not participating in the election this time. For a long time, these parties have been considered the primary means of political representation for the hill or indigenous voters. As a result, in the absence of their candidates, both competition and participation in the election have declined.

According to locals, elections in the hills previously meant intense political excitement. There used to be spontaneous voter presence in support of regional parties. But that scene is absent this time. In many areas, campaigning is limited, public gatherings are small, and there is a lack of visible activists and supporters in the মাঠ. As a result, instead of a festive electoral atmosphere, there is a sense of stagnation.

Rangamati is the largest district in the country and has more than five hundred thousand voters. A large portion of them belong to ethnic minority communities. Historically, this vote bank has been loyal to regional parties. In 2014, a JSS candidate won, and in the 2024 election, in the absence of the party, voter turnout was extremely low in many centers at some centers, no one even went to vote.

A section of voters say that without regional parties, they cannot find their own representation. As a result, their interest in the election decreases. A young indigenous voter at College Mor in Rangamati town said, “Our main demand is peace and harmony. But those who understand the reality of the hills are not even in the field. Then what is the point of voting?”

On the other hand, recent violence, conflict, and security concerns in the hills are also affecting the electoral environment. The tourism-dependent economy is being repeatedly damaged. Local businesspeople say that development is not possible without stability. Although they have no interest in who wins or loses since indigenous parties are absent, they at least expect that whoever wins should ensure peace first.

With the absence of regional parties as the main force, the main contest this time involves the BNP and Jamaat alliance along with several national parties. However, observers believe the election is not becoming competitive due to the lack of strong regional rivals. Analysts say that without a participatory and inclusive election, the acceptability of the results may also come into question.

The administration has stated that election officials and materials will be sent to remote areas by helicopter. Security will include the army, BGB, and law enforcement agencies. But more than security arrangements, the bigger question has become voter participation.

Overall, this year’s election in the Chittagong Hill Tracts is not one of festivity, but rather of apathy and uncertainty. How representative and competitive this regional party-less election will be—that is now the central topic of discussion in the hill communities.