Begum Rokeya’s 146th Birth Anniversary

A Vision of Non-Communal, Humane and Scientific Society

Today marks the 146th birth anniversary of Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880–1932), a pioneer of women’s awakening, an educationist, and a writer. The imagination of a non-communal, inclusive, and science-minded society that she presented a century ago remains equally relevant today. The philosophy she upheld—to overcome communal conflict, gender discrimination, and social crises and build a humane, educated, and progressive nation—was reflected in every layer of her writings and active life.

From the Swadeshi movement during the Partition of Bengal (1905–1911) to Gandhi’s Swaraj movement, South Asia was aflame with religious hostility and divisions. Communal riots in Dhaka, Kanpur, Kashmir, and Vellore were part of her lived experience. Yet she never lost faith that without Hindu–Muslim unity, it would be impossible to build a modern, peaceful, and prosperous India (and today’s Bangladesh).

Deeply religious though she was, Rokeya was never communal. While Qur’an reading, regular prayers, and the liberation of Muslim women were central to her work, she always emphasized the broader freedom of all women. This is why, in 1911, when she founded a school in Kolkata for Muslim girls, she regularly visited Brahmo and Hindu schools to gain experience. There she built lifelong friendships with educationists like P.K. Ray. After her death, at the memorial meeting held at Albert Hall, people of all religions came to honor her. Presiding over the meeting, P.K. Ray said, “She knew that mere rituals are not religion; true religion is human welfare.”

Her writings clearly reflect this non-communal consciousness. In the essay “Sughrihini,” Rokeya wrote, “We are first Indian, then Hindu–Muslim.” Again, in her essay “Educational Ideals for the Modern Indian Girl,” quoting the Upanishads and the Gita, she stated that along with adopting the good elements of one’s own tradition, Western knowledge needs to be integrated to modernize education. In this way she offered a vision of a synthesized modernity, combining East and West.

Hindu mythology and goddess figures appear in her writings, as do the shared struggles of Hindu and Muslim women. In works such as “Nari Srishti,” “Sristitattva,” “Nurse Nelly,” “Nari Puja,” “Griha,” and “Abarodhbasini,” we see the common experience of Hindu–Muslim women confined within the same system of oppression. She made it clear that the condition of women does not differ by religion; patriarchy everywhere has taken away women’s rights.

Her non-communal mind was intertwined with a global sense of solidarity, love, and humanity. In her story “Premrahasya,” she wrote, “I love people of all religions—Hindu, Christian, Muslim.” In her personal life, she built deep bonds with a Dalit girl named Champa, an English woman, and an elderly woman from northern India.

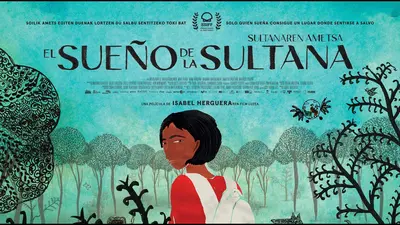

The highest expression of Rokeya’s progressive imagination appears in her science-based speculative story “Sultana’s Dream,” where women scientists discover solar-powered technology, flying vehicles, weather control, and automated agriculture. In today’s era of smart technology, these imaginations seem remarkably close to reality.

Being born and dying on the same date—December 9—is indeed rare. On the night before her death, she was still writing about “women’s rights.” Until her last breath, she worked for women’s liberation, education, and the creation of a humane society.

On her birth anniversary today, one question remains: Have we been able to move toward the non-communal, humane, and science-minded society she envisioned a hundred years ago?