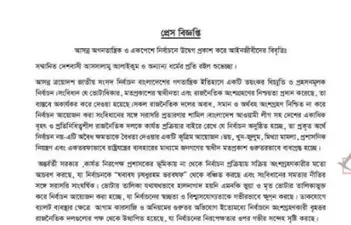

Government Moves to Control All Internet Services Under New Telecommunication Law

Not only telephone or mobile operators, but from now on all internet‐based services will come under government control. International platforms like Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp or Netflix will also need government approval if they wish to provide services in Bangladesh. With certain conditions, interception will be possible. With such provisions, the government has initiated an amendment to the 2001 Telecommunication Act.

In this context the Department of Posts and Telecommunications has drafted the “Bangladesh Telecommunication Ordinance 2025”. For this it has sought stakeholders’ views. Once this law comes into force, the colonial-era Telegraph Act 1885 and Wireless Telegraphy Act 1933 will be repealed.

A joint secretary of the telecommunications department, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said that the 2001 Act was primarily limited to licensing, services and oversight structures for mobile operators. At that time mobile phones were a luxury and the internet was at a primary stage. But over two decades Bangladesh’s communications system has changed. Now people don’t just talk on the phone—they rely on social media, video platforms and messaging apps. The existing law cannot oversee a modern communications system. That is why a new law is being introduced, under which telecommunications as well as internet, social media, over-the-top (OTT) services, video streaming, artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT) will be subject to oversight.

Social Media Registration Mandatory

For the first time the draft law states that any online platform (such as Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Netflix or TikTok) that provides services in Bangladesh must get government approval and registration. If required, they must provide information to security agencies and comply with the government’s instructions on user-data retention. In other words, foreign OTT platforms will now fall within Bangladesh’s legal framework.

Experts say that on one hand this will ensure accountability for the state, but on the other hand it could impose new controls over freedom of expression. It may raise concerns for privacy and freedom of speech. Technology expert Suman Ahmed Sabir says that while surveillance is necessary, turning into control is dangerous. He advises the law should not shrink the space for freedom. He says the draft provides no guarantee of citizen data protection. And yet information is now a source of power. Without a balance between security and personal freedom, this will become a law of a surveillance state. He further says that many parts of the draft are still ambiguous: what conditions online platforms must meet for registration, what measures will be there for data protection—these are not clearly stated.

Suman Ahmed Sabir believes that the new law is timely but in its implementation framework balance is essential.

Interception with Conditions

In the new draft, provisions for interception or communication surveillance with court-approval and certain conditions have been included. Under clauses 97 and 97(b) of the draft, for state security, public order or criminal investigation a court or an authorised council can order collection of communication, message or traffic data for a specified period. A Central Lawful Interception Platform (CLIP) will be set up for this purpose, which will be operated under the home ministry. With court approval, intelligence and security agencies will be able to collect needed data for a specified period via this platform.

The draft further states that “once a mechanism under this clause becomes effective, the previous interception-related mechanism will be deemed repealed.” That is, the existing National Telecom Monitoring Centre (NTMC)’s activities will be replaced by the new CLIP platform.

New Commission, but Powerless

In place of the current Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC), a new Bangladesh Telecommunication Commission will be formed. It will be declared a constitutional body. The commission will have five members—one chairman, one vice-chairman and three members.

In various clauses of the same draft it is observed that the commission’s powers have been reduced and made dependent on the government’s policy-directives. In the 2001 Act BTRC was a self-governing and independent body; it had power to issue licences, manage spectrum, regulate, investigate and even impose penalties. The new draft states that “the commission shall follow the government’s policy and directives in decision-making.” For issuance and cancellation of national important licences a five-minister committee will work. Further, to ensure the commission’s major tasks and accountability an eleven-member “Transparency and Accountability Committee” will be formed. This committee will discuss big tariffs, licensing matters before the government approval is sought. So, how independent the commission will be remains in question. In the words of a former BTRC commissioner: “A name change cannot bring independence if policy-power remains in the government’s hands.”

Technology entrepreneurs say that if registration and approval processes become overly complex, new ventures or startups may be hindered. Tech entrepreneur Mustakim Billah says the more complex the licensing process, the slower innovation will be.