No Asset Declarations from Yunus Government Advisers Even After One and a Half Years

Upon assuming power, the interim government made sweeping promises of “zero tolerance” for corruption and a new era of transparency. In his first address to the nation, Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus declared, “All advisers will disclose their asset statements within the shortest possible time.” At the time, many believed Bangladesh was on the verge of a new political culture.

More than a year and a half later, reality tells a very different story. Not a single adviser’s asset declaration has been made public. The question now being asked is whether those promises were merely rhetorical.

Ordinary citizens trusted that the interim government under Professor Yunus would set a benchmark for accountability. Instead, what has emerged is a pattern of verbal commitments to transparency coupled with secrecy in practice.

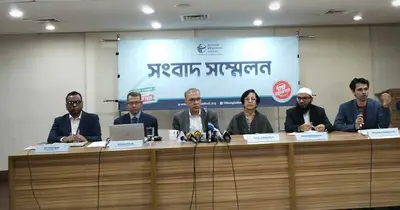

Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) Executive Director Dr. Iftekharuzzaman has described this failure as “regrettable,” saying the public did not expect such opacity from a government that came to power pledging accountability. Economist Dr. Debapriya Bhattacharya, considered close to the Yunus administration, has also warned that keeping asset declarations secret would set a dangerous precedent for future governments.

In effect, the conduct of this government risks becoming a ready excuse for future ministers and officials to argue, “They didn’t disclose either—why should we?”

The issue becomes even more pointed when government policy is examined. In October 2024, the interim government issued a gazette notification mandating advisers to submit income and asset statements within 15 working days of filing their tax returns, with the chief adviser responsible for making the information public.

So why has nothing been disclosed?

This is where suspicion begins. Political analyst Mahfuz Anam has described the pledge as potentially nothing more than a “symbolic stunt.” If the information is clean, what is there to fear from disclosure? Or would publication invite uncomfortable questions?

These doubts have been reinforced by a series of allegations against advisers. Within months of the government’s formation, former secretary ABM Abdus Sattar publicly accused at least eight advisers of “unchecked corruption,” claiming that key appointments and transfers required advisers’ backing. The government dismissed the allegations as “baseless,” but no visible investigation followed.

Later, a video circulated on social media showing alleged extortion at the residence of Awami League leader Shammi Ahmed, with the name of then Local Government Adviser Asif Mahmud Sajib Bhuiyan becoming entangled in the controversy. Although he denied the allegations, there has been no visible progress in any independent investigation.

Even more strikingly, several personal officers and assistants to advisers were removed from their posts after allegations of corruption involving millions of taka were found to have initial merit. This raises an obvious question: if a close aide to an adviser is implicated in corruption, can the adviser themselves escape responsibility?

TIB maintains that advisers cannot evade accountability for the conduct of their subordinates.

Yet an apparent “culture of denial” seems to have taken root within the government allegations are denied, criticism is met with silence.

Fresh controversy has also emerged around Grameen-related issues. Analysts have raised concerns over potential conflicts of interest involving tax exemptions for Grameen Bank, reductions in government shareholding, approval of a new university, and the granting of a digital wallet license institutions linked to Professor Yunus. No clear answers have been provided as to whether such benefits meet ethical standards while he remains in power.

As economist Professor Anu Muhammad put it, “Holding power itself is sufficient to exert influence.” In other words, influence does not always require documentation; circumstances often speak for themselves.

Advisers claim they have submitted their asset statements to the Cabinet Division. But when will the public see them? The argument of “we have submitted them, but won’t publish them” runs directly counter to the principle of transparency. How can a government funded by taxpayers justify keeping its leaders’ asset information hidden from the public?

Former adviser Nahid Islam has disclosed his asset information through an affidavit, though questions remain about its clarity, and the disclosure appears to have been driven solely by electoral requirements. The asset declarations of other advisers remain concealed.

As the tenure of the interim government nears its end, failure to publish asset declarations would undermine all claims of moral authority. A government that came to power promising to fight corruption cannot credibly justify hiding its own financial information. This is not merely hypocrisy it is a betrayal of public trust.

Even at the final hour, the opportunity remains. Disclose how much advisers owned upon assuming office and how much they own now. Otherwise, history may record that while the promise was transparency, the reality was a wall of deception.